Emerging electronic media , although transformative in many ways, are not reinventing our relationship to books. As with any change in the human environment, polarizing opinions tend to dominate ways of understanding. This will obscure genuine trends, making it harder to imagine what a book in 2015 might look like. First it might be best to observe the historical book of yesterday.

Books, as a communicative form, have maintained a dominance over informational authority, dissemination of meaning, and community imagination across a global culture for centuries. The dynamism of oral historical transmission is not possible once the word is written down, but almost every other significant intellectual and relational human development is arguably attributable to the book. Religion is able to define values and right behaviors, lawmakers are able to establish precedent, merchants are able to codify national and international bartering systems, and policy makers are accountable to history. Once Averroes (nee Abul-Waleed Muhammad Ibn Rushd) reintroduced the West to Aristotle, a revolution of individuation began which we continue to work through to today.

from St. Matthew, from the Gospel Book of Charlemagne, c.800-10.

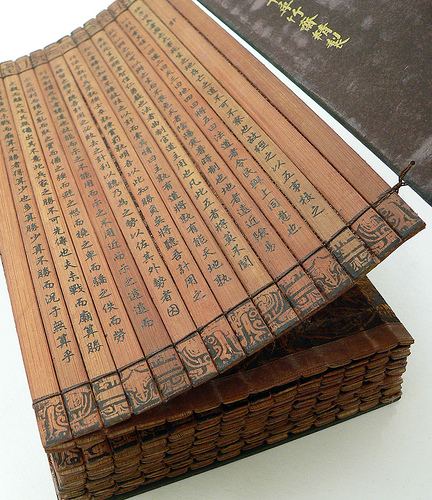

Manuscripts were instrumental in this, yet without standardization, context and meaning could change. The first widespread re-imagining of the book occurred with Gutenberg’s movable type. (Though China achieved this with baked clay over 400 years earlier, the basic realities of Chinese script prevented common use.) The Gutenberg Galaxy as Marshall McLuhan labeled it, enabled text to be set in a way previously not possible. As more and more copies of a work were produced, identically and rapidly, paradigmatic precedents could be more quickly established. People were able to communicate more effectively, much like the initial standardized catechisms for Christians, yet more personally and frequently.

The manipulation of meaning in a written work prior to printing presses has never entirely gone away, though it was slowed for a time once editions numbered in thousands. Anxiety about losing authoritative, factual information is justified, especially in a world where entities such as Google are becoming global repositories on an unprecedented scale.

Yet this anxiety must be contextualized. The West, circa 1200a.d., did not even know what it was missing until Averrose translated Aristotle. How many books are really in the Bible? And written by whose hand? Absolute meaning is illusory, a reflection of a human need more than an accurate representation of truth. This scientific, rational age is dependant upon the assumption that facts, once discovered, are eternal. Books reflect all dimensions of human experience, and their authority is granted by a wish for it to be so. Through neglect, propagandism and selectivity, meaning is negotiated over time.

from Bored.com Crazy and Funny Billboards

Part of the problem with wondering about books’ future is that historically the idea of what a book is has changed. For me, today’s eBook is akin to the copying of books by monks from Charlemagne’s time until the printing press. Manuscripts would change, depending on the inclinations of the monk, his attentiveness, or even the physical degradation of the source text. Something like Wikipedia, though materially sped up, is as malleable as a handwritten manuscript.

Our imagined book is fixed in time, a static recitation of alphabetic or logographic symbols. This is a very limited definition of what a book is. For Max Ernst or Paul Eluard, a book might be a collection of collages in lieu of words. For Alexsandr Rodchenko, a book may contain coins, twine, letter pressings and glass. For Katsushika Hokusai, a book may be a printed fan, a single sheet of paper bound accordion-style, or even a tiny box of lithographs centered on a single theme. The “Museum of the Book” already exists, and even did as a concept in the time of Charlemagne, when he sought to re-establish the lineage of Roman philosophy nearly lost to Visigothic and Vandal raids.

The question then might properly be “What is the possible effect that digitalization will bring?” The primacy of books can be attributed to many factors: portability, accessibility, affordability, durability, familiarity, and readability, among others. Until digital means can approximate or replicate all of these conditions, books as physical artifacts with paper bones and inky blood will not be replaced.

Portability for electronic books is on the verge of realization, as is accessibility. Affordability? Maybe not. Durability is unlikely, considering that many manufacturers rely on either inferior craftsmanship or software updates to ensure a continual need for purchasing new equipment. Familiarity can only be established over time. A foremost concern is readability, for though the human eye will adapt to longer exposure times to electronic stimuli, it remains difficult to enjoy an electronic work for as long a time as one can a book.

Moving images will survive, though perhaps that is too young a model. Music has undergone about as many transformations as the written word, be it private amusement, communication, traveling minstrels, orchestral engagements, wax cylinders, vinyl and digital storage. Books will continue to thrive, fluidly, stubbornly, but mainly out of necessity.

Posted by Vaucanson's Duck

Posted by Vaucanson's Duck