“As yet no one can give much account of what is taking place in your head as you read this sentence.” (Robinson, 217)

Language creates free-floating maps in our minds, chains of association and memory which can be liberating and controlling at the same time. Many linguists imagine that the hardwiring for language already exists, perhaps already evident in utero, certainly siphoning understanding from ambient environments right from the moment of birth. Others have hypothesized that our ability to integrate language is due to complex symbiotic chemical relationships fostered by either dietary or religious/shamanic habits we developed over centuries.

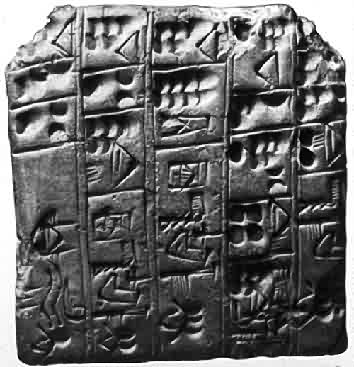

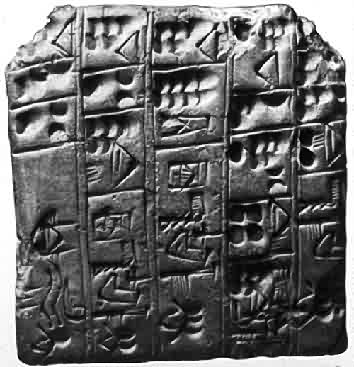

A more rationalist view proposes necessity. The earliest extant writings we have, Sumerian clay tablets from Mesopotamia, list products such as barley, beer and labourers, as well as fields and their owners. A writer discussing the Sumerian tablets commented that writing developed “as a direct consequence of the compelling demands of an expanding economy.” (For example, check out the writings of Orville R. Keister for details) This explanation for the origin of language does make a lot of sense, even considering the loss of many early writings which were on perishable materials or neglected by the dust-broom of history. Necessity does not preclude the hardwiring theory, since it takes time for the brain to create new memory system mechanisms. This still leaves open the question of how language originated out of a state of no language.

The artistry of many early pictographs, hieroglyphs, and cuneiform writings, as well as proto-Elamite and ancient Chinese scripts is undeniable. Writing even from the beginning, before any system coalesced into standard forms, to my mind evidenced more than a simple desire for record keeping. Examples of proto-writing (meaning systems of record keeping and notation that do not use rebuses, logograms, phonograms etc), such as the tablet from the office of Kushim, were a mixture of numeric records and personalized renderings of everyday goods and services.

It was not long, only a few hundred years at the most, before the Egyptians begin to use hieroglyphs and Demotic to write spells, commune with the Gods and boast of prestige, statue and wealth. They chose not to adopt just a purely alphabetic uniconsonantal script, the beginnings of which already existed, whether to preserve the mystery of sacred rites or to more accurately reflect the reality of the language is not known. Once the miracle of writing took root, humans jealously protected their cumulative knowledge and sought influence through strategizing trade and warfare, while enjoying the sacred and contemplative facets of language as well.

Writing continued to develop across numerous continents and cultures through elaborate channels of trade and conquest, and different cultures experimented with phonemic, syllabic, logographic and consonantal systems. Right to left, left to right, top to bottom…various reading and writing orientations might show up in the same culture, even in the same document. (My favorite system is boustrophedon, or “as the ox plows a field,” where a line of writing would reach the end of a page or a tablet and the surface would be turned 180 degrees before the writing would continue) Are the physical demands of our brain in learning language and writing different than of systems of thought which came before?

Modern studies of writing’s development would often discuss its correlation to speech patterns. “Until the last few decades it was universally agreed that over centuries western civilization had tried to make writing a closer and closer representation of speech…Scholars – at least western scholars – thus has a clear conception of writing progressing from cumbersome ancient scripts with multiple signs to simple and superior modern alphabets. Few are now as confident.” (Robinson, 214-215) In truth, we are developing new communicative languages, continually supplementing and expanding our functional repertoire.

Language is fundamental to culture, identity, consciousness and memory in a way that makes it ideal fodder for scientific experimentation. Early Greek scholars imagined that the brain secreted fluids, or spirits, to communicate. We now know much more about electrochemical charges in the neural pathways of our brains. Biologically, electrical currents are transmitted through ions, much like the movement of electrons in wire. “In terms of operation, a neuron is incredibly simple. It responds to many incoming electrical signals by sending out a stream of electrical impulses of its own. It is how this response changes with time and how it varies with the state of other parts of the brain that defines the unique complexity of our behavioral responses.” (Regan, 20)

As science begins to narrow down communicative networks in the brain, and close in on systems of post- and pre- synaptic neurotransmissions, concentration on both genetic and chemical cartography has intensified. Just recently several scientists have brought a bit of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind to life by developing a drug to banish bad memories. “We generally think of memory as an individual faculty. But it is now known that there are multiple memory systems in the brain, each devoted to different memory functions.” (Regan, 77)

Think about the story of Phineas Gage. After an accident on a Vermont railroad site around 1849, Phineas was left with a hole through his skull and missing a portion of the ventromedial region of his brain. He recovered fairly quickly, and reportedly did not lose consciousness in the moment, standing upright just after the accident and asking about work. Previously a reliable and amiable foreman, afterward he was prone to fits of rage and profanity. The oft quoted refrain from his friends is that he was “No longer Gage.”

Clearly cases such as his led to John Watson’s development of the behaviorist school of psychology in the 20s, most popularly understood through the work of B F Skinner and his book Walden Two. And behavioral psychology, with its emphasis on observable phenomena, still exerts power over our modern philosophical approach to consciousness, even if research into the genome is recontextualizing the discussion. Craig Venter, a primary architect of genomic sequencing, said in 2001 that “In everyday language the talk is about a gene for this and a gene for that. We are now finding that that is rarely so. The number of genes that work in that way can almost be counted on your fingers, because we are just not hard-wired in that way.” Interestingly, he is working on developing designer microbes to combat our oil addiction; is this the beginning of nanotech wetware?

Earlier today I was working on an assignment for a class of mine, trying to encode several web pages that will, at the end of the last session, go live on the web. I lost all my files somehow and had to reconstruct what I could, while finding the pool of images I initially discovered to supplement my topic. I searched through Flickr’s library of creative commons licensed photos, scanning mercilessly for inspiring and beautiful photos. At the end of a half hour I think I perused over 3000 photos, and I was struck by both my pace and my faculty for recognition. It’s just unbelievable to me how effective our discriminatory abilities are, how abstract and correlative. How is it that we can know so quickly what appeals to us, or what meets any particular need at a particular moment?

So much of what we call Web 2.0 uses cooperatively communicative tools for discrimination. We are rapidly developing unique languages for linking machines, humans and the natural world into electronic ecosystems that are often self-sufficient and collectively interpreted. It’s an amazing irony that we are returning to hieroglyphic, or rather logographic, linguistic roots with a dedicated fervor, reimagining language for the benefit of communication across normal linguistic divides. This is evident both in the programming languages that comprise the design of Internet forums as well as graphic symbols for travelers and efficiency in communication.

Both gypsy and hobo communities have made extensive use of logograms, and even Olympic committees have tried to bridge cultural divides through ideograms. (Let’s try to forget the horrible 2012 design from England…) Advertising at its root is most effective in establishing branded identities which can achieve the iconic status of a letter or character; the favicon is rapidly becoming a digital fingerprint essential to the establishment of one’s Internet identity. Is recognition of these signs any different neurally than reading in our native tongue?

Language has been accused of engendering psychosis, most notably by English psychiatrist Tim Crow. Language makes use of both hemispheres of the brain, though it is theorized that the left lobe is more fundamental; where the right hemisphere is responsible for reading words, the left hemisphere contextualizes meaning rather than just visual appearance. Tim Crow feels that psychosis (and specifically schizophrenia), which is associated with high levels of neurotransmission in the right hemisphere, is the price of learning language. “Given that psychosis is universal, affecting all human populations to approximately the same degree, and that it is biologically disadvantageous, there must be some reason why it has persisted.” (Regan, 109) Who knows? It’s likely that only the continued development of highly specialized pharmaceuticals will answer his hypothesis.

Crow’s idea is quite possibly a causation fallacy, but I am not qualified to hazard a guess. Memory is central to our consciousness, and language makes use of so many aspects of memory. Michel Foucault has stated that “Language is the first and last structure of madness, its constituent form; on language are based all the cycles in which madness articulates its nature.” What does this mean for the intensified rate of language extinctions brought on by population growth, complex economic interdependency and radical exploration for resources? Or are we developing new forms of communication so quickly that it will counterbalance any loss of classical alphabets and character sets? Perhaps memory will be externalized as we develop new skills for increasingly abstracted electronic environments. “…if our memories are to remain, then some physical change must occur–memory cannot be imprinted on molecules since molecules are constantly rejuvenated by the body at different rates.” (Regan, 80)

The brain is remarkably flexible when it comes to long term memory. Working memory, which is incorrectly believed to be “short-term memory” but is more akin to a mental sketchpad (to use Alan Baddeley’s term), uses the prefrontal cortex. But for longer term memory the architecture of the brain is quite individuated depending on different needs; it is believed that the cortex is the final home for information and memory, and the hippocampus is intimately involved with processing what will become long term memories. Long term memories may require dendritic growth and the formation of new synapses. Interestingly, “learning a foreign language in adulthood employs a brain area that is distinct from that used in establishing one’s first language.” (Regan, 83)

In many ways the Internet, through for example eBay, Craigslist and Google AdSense, is returning graphic communication to its accountancy roots; along the long tail, each of us is a nested market of one, with the power to shoulder the vender’s yoke as well. As levels of interconnectivity flourish online, and many millions of text messages are transmitted daily, we are no closer to understanding the relationship of our digital media to the cultivation of memory. The Internet, for all its novelty, is possibly recreating the elemental genesis that inspired language in the first place, but what we gain in immediacy may be lost in the flurry of information.

In the end I am left wondering, what is the signal-to-noise ratio for language today?

books cited:Robinson, Andrew. The Story of Writing. Thames & Hudson, 2nd edition 2001.Regan, Ciaran. Intoxicating Minds: How Drugs Work. Columbia University Press, 2001.

Posted by Vaucanson's Duck

Posted by Vaucanson's Duck